A Day in the Life of a Chicago Public School Student

A piece from “Chicago Retold” — A project on the violence in Chicago.

by Amy Schuett

Who wants to read the board?” The invitation strikes fear into the heart of Mexican-Puerto Rican high school junior Maria, who sits with her head bowed on her desk to avoid being called on.

“I will read, but if I can’t say the word, then I will just give up on it,” she says. “It makes me get irritated quick because I cannot do the work if I don’t understand something, and I just won’t do the work ’cause I don’t know what to do.”

Maria (name changed to protect subject’s identity) is one of many Chicago Public School students who have difficulty reading. Although she is a junior in high school, Maria reads at a second or third-grade level. The U.S. Department of Education found that, “Seventy-nine percent of eighth-grade students in the Chicago Public Schools were not grade-level proficient in reading.” Some even graduate without the ability to read an elementary-level chapter book or fill out a job application.

Every day, Maria rides the bus for an hour from her neighborhood, Back of the Yards, to Wells High School. Her headphones blare Norteña, a type of Hispanic music, until the bus pulls into the parking lot.

Royal blue lockers and fluorescent hallway lights make Wells appear almost identical to other American high schools, but Maria and her classmates are greeted each morning by a metal detector and security team.

Students walk to class as the bell rings at Wells High School.

As first period begins, Maria reaches inside her backpack for a pencil and comes back empty-handed. She doesn’t have any school supplies. Like Maria, many students lack basic supplies like pencils and paper and look to the school to provide them.

Lack of government funding creates problems for Wells and other CPS schools. Schools may close early due to low budgets, and summer school programs are on the verge of being cut, which would save CPS over 90 million dollars, reported by CBS Local.

Teachers make do with broken and outdated technology; books are lent out for a class period but are too few in number for students to take home. Generally, teachers end up providing the supplies for their students and classrooms; some even shell out thousands of dollars per year from their own pockets.

According to Wells High School Principal Rita Raichoudhuri, the decreased funding Wells receives makes it difficult to care for her students. “Schools that serve in the poorer areas do not get equitable funding,” she says. “Students who need more don’t get more.”

“Schools that serve in the poorer areas do not get equitable funding. Students who need more don’t get more.”

-Rita Raichoudhuri

Not all students within the district boundaries go to Wells. Some choose to attend charter or other alternative schools. Because this decreases enrollment at Wells, the public school’s funding drops, too. Between the students at alternative schools and the students who are not accepted, cannot afford, or are kicked out of alternative schools, a rift grows, Raichoudhuri explains.

“It causes a class system,” she says. “It very much creates a divide in society, which gets perpetuated from an early age because of how our school system is structured.”

Wells High School

Wells students come from a variety of home backgrounds; many are from low-income and single-parent high schools, several students are homeless, and some live apart from their parents.

In addition, a large percentage of the Wells population is composed of English Language Learners (ELL) students, as well as many students with Individualized Education Plans (IEPs) for learning disabilities. Fifty-two percent of students are African American, 47 percent are Latino/Hispanic, and a small number of students are Eastern European refugees.

Despite the diversity of students’ ethnic and economic backgrounds, reading is a problem almost across the board. And for students with IEPs, like Maria, the lack of funding is particularly troublesome.

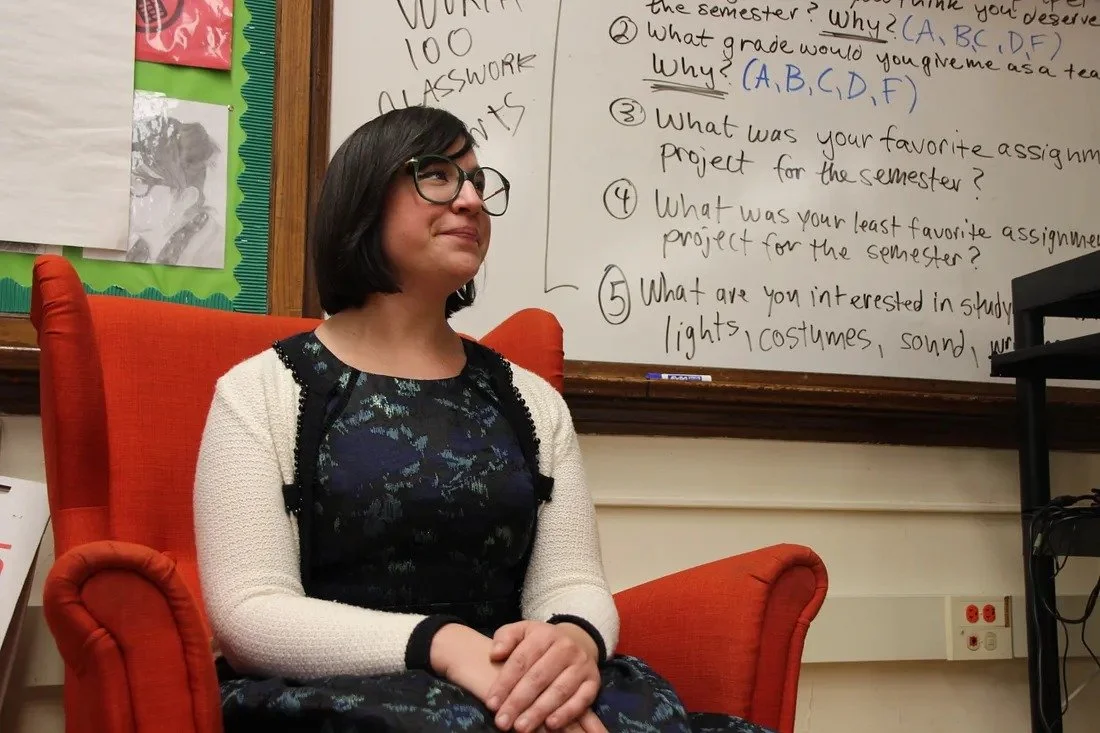

Wells teachers work hard to prioritize literacy. English teacher Caitlin Scheib said, “[Literacy] is such a huge focus…Very few [students] come at grade-level or above.”

Scheib spends hours of her personal time crafting lessons that both engage students and develop their literacy skills. Her English class is studying the Broadway musical Hamilton, reading the lyrics to each song, analyzing the words and writing responses. When Scheib first started this practice, her students struggled to finish one song in a class period. Now, they can listen to three songs and complete a full analysis before the bell.

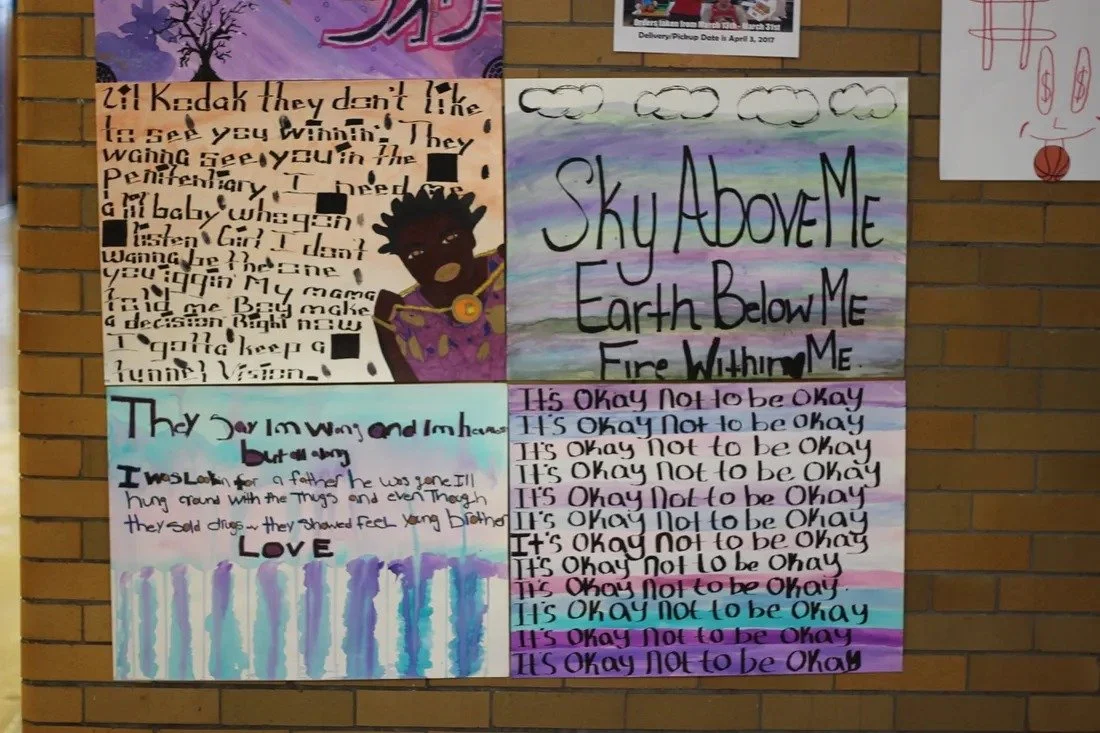

Art students love being creative with words and colors.

“Great job, Carlos! Full participation points for the day!” Scheib says to one of her students, high-fiving him on the way out. He leaves the class smiling after answering all the questions on his worksheet. Usually, Carlos struggles to complete tasks, but with direct focus and personalized attention, he is able to work to his full potential. By honoring students and getting creative in her teaching methods, Scheib actively combats the illiteracy plaguing Chicago youth.

In the past year, budget cuts have been tough on teachers. Administrators at Wells were compelled to lay off teachers, aides, and even the dean due to lack of funding.

Students like Maria are concerned by the growing class sizes and decreasing number of teachers. “There’s so many kids that need help. It’s hard [reading] because some teachers don’t really help us,” Maria said, pausing momentarily as she struggled for words. “Like they do, but they don’t give us too much attention ’cause they gotta help the other student. Especially…the special kids that need help for reading and writing.”

Thankfully for Maria, she did receive help. Last year, a volunteer from a para-church organization came and sat with her in classes. The teacher specifically paired the aide with Maria to work on her reading.

“At first, when I didn’t have anyone to help me, I was at a low F,” Maria remembers. “[The volunteer] helped me with my work, and my F went to a D, until I finally got it to an A.” She smiled and looked down. “I feel great because I never had that help before. I didn’t know if I should say I needed help because I was shy.”

“I feel great because I never had that help before. I didn’t know if I should say I needed help because I was shy.”

-Maria

However, like most students, Maria does not receive educational support at home. Her father is slowly going blind, while her mother works to provide for not only her immediate family, but also for Maria’s extended family members who live in their upstairs apartment. School is the one place that Maria has the opportunity to read, yet some days she has no one to help her with the “hard words,” she said.

At school, outbreaks of violence can distract students from learning, too. At lunch, Maria’s good mood over “pizza again!” quickly turns to disapproval at the sight of two girls arguing loudly nearby. “Girls, always girls,” she sighs.

These arguments usually start on Facebook the night before and trickle into the following school day. Some days, they escalate to a physical fight. Wells faculty and staff respond as best they can to these situations. Maria was once in an argument, and to avoid a fight, she was asked to sit and talk things through with the school social worker.

However, Wells staff do not catch all the fights. Videos appear on social media, and students cheer on the violence. Comments such as, “I’m gonna beat that THOT (that hoe over there) tomorrow,” or “I beat that b — a — today and I will do it tomorrow,” are examples of how some students interact with one another on social media.

Principal Raichoudhuri invests a lot of time and energy in students who are susceptible to gang involvement. “Fewer students are in gangs because of after school programs and one-on-one mentorship programs such as GRIP the School,” she says. “We still have students in gangs, [but] we don’t really see much of that manifesting. The culture that we have created is a safe space.”

As Maria enters her final class, she dreads the thought of going home and struggles to do her work. “I feel depressed because all the stuff I go through, I can’t focus” she says, her head once more on her desk.

This problem does not go unnoticed by the teachers and faculty. “We have students coming to school [who have] experienced some sort of trauma, and go back to home life with abuse. [They] come with lots of social and emotional problems,” Raichoudhuri says. This makes teaching them all the more difficult.

Scheib also notices the burdens her students carry to school. “They can’t possibly be focused on academics when their needs aren’t being met.”

Caitlin Scheib poses in her classroom.

In light of this, Scheib makes it a point to treat her students with honor and dignity. “How can you expect them to do work when they aren’t being honored and taken care of?” Scheib wonders out loud. “There are so many issues they are dealing with that could be affecting their academic work. They are unfocused, hurt, scared.”

As the school bell rings, students thunder from classrooms for their lockers.

“Be safe,” Maria yells down the hallway.

“Be safe, girl,” her friend responds.

These words echo through the hallway as students remember the reality of the violence to which they are returning: violence in their neighborhoods, in their streets, and for some, even in their own houses.

Maria keeps track of what is going on in her neighborhood, sharing articles on social media detailing the shootings and deaths in Back of the Yards.

“I was walking home and this gang banger came up to me and he said, ‘You’re next b— ,’” she said. “I don’t feel safe there…and there are too many gangs in each corner. So they be shooting, and they don’t mind if you’re a kid, they will shoot you.”

Every day Maria wonders if something will happen to her loved ones while she is at school. “I hear a lot of gunshots… every week, weekends and weekdays,” she says. Lowering her eyes, she adds, “I lost three of them in my family and then friends.” She worries every morning on her way to school that she may have seen a family member for the last time.

“I’m always surprised when a student starts telling me their story,” Scheib says. “I’m shocked with the trauma they are bringing in to school, seeing someone shot. They just state it like it’s normal fact.”

“I’m shocked with the trauma they are bringing in to school, seeing someone shot. They just state it like it’s normal fact.”

- Caitlin Scheib

Yet for all their professed strength, students are still affected tremendously by the violence, Scheib says. Last year, a popular student was shot and ended up in a wheelchair. “For the students to see him the first time you could physically feel their shock and their realization, ‘He is just like me, and now his life is totally changed,’” she says.

Faculty at Wells High School realize the burden violence places on students and attempt to address the underlying causes of student misbehavior. “Instead of just punishing, [Wells is] trying to figure out what’s going on and what’s happening and deal with it,” Scheib said. “Students need skills to manage trauma, hurt, burden, these things that are just a part of their reality.”

Teachers like Scheib work hard to provide in their classrooms a safe and healthy environment for students. Scheib sees this type of atmosphere as a glimmer of hope for students. “They have to find community here (at Wells),” she says. “Maybe the community at home is what they are trying to escape. They need to find the community that resonates with them here, either academic, or an after school group. If the lowest [achieving] student can find their passion, it can keep them coming to school.”

Principal Raichoudhuri has hope for the future of her school. “Often, adults don’t invest in [students] because they don’t think it will make a difference,” she says. “They will think this student is so broken, their home life is so horrible, that no matter what we do, it’s not going to change outcomes for this student.” Her goal is to help other adults see the potential in these students and believe they can make a difference.

What stands out to Maria when she thinks of her school isn’t the lack of pencils, the girl fights, or her reading struggles — it’s the volunteer who sat with her to read.

“I did better in my reading and writing. I was happy because I’d never had the help that she gave me. It was something special that she did [for] me,” she says.

Maria’s advice for the future? Simple: bring in more volunteers to help students.

“It feels great,” she says. “I feel proud of myself because I didn’t know I could make it. And I did.”