The Complex Relationship Between Chicago’s Police Department and Residents of the City’s Most Violent Neighborhoods

A piece from “Chicago Retold” — A project on the violence in Chicago.

by Rachel Naffziger

David Johnson grew up in Englewood. Things started out positive, he said, but “one door led to another,” and he got involved in fraud and drug dealing. He was incarcerated twice. During the first incarceration, some fellow prisoners prayed for him, telling him, “You gonna be a mighty man of valor, with a heart for children and youth.”

Once he got out, it took him only 40 days to get incarcerated again. The second time, a visiting chaplain came in three times a week to talk with him. Long story short, Johnson (name changed to protect subject’s identity) came out of the prison a new man. Now, he is married with children, active in church, and works mentoring youth.

Not long ago, Johnson was pulled over, in his words “without reason”. The cops took his license and registration, but instead of going to check them, they asked him to get out.

Johnson had seen police violate constitutional boundaries more times than he could count, so he did not want to put himself in a vulnerable position by getting out of his car. He knew his rights, and stated them. One of the officers became hostile and verbally abusive, and as Johnson put it, “They went AWOL.” They beat him badly, planted drugs on him from another bust, and arrested him. “Police need to meet a quota, just like anybody else,” he explained. And he had ticked them off.

However, Johnson used lawyers and his connections to push back, appealing to the courts. His case is doing well, but had he not been working for the very advocacy organization now protecting him, he would be in Cook County Jail seven years, with a bond of over $100k. To Johnson, “seven years in Cook County is like seven years in hell.”

Cook County Jail is located not far from the heart of Little Village, a primarily Latino neighborhood on the west side.

“Strife and contention arise…”

Some time after that arrest, Johnson told the story to the founder of the organization where he mentors youth.

“He told me, ‘David, if you hadn’t told me your story, I never would have believed that cops do this kind of thing.’ He said that right out of his mouth!”

Johnson was incredulous. He wondered how could there be such a gulf between his perception of the police and that of a prominent leader in the urban ministry.

Dr. Beverly Reid, a former high school principal and sociologist, has also pondered this gulf. She paused to chat at one of Moody Bible Institute’s booths during Founder’s Week. As an annual roundup of conservative evangelical preaching, the conference is not the place people go to talk against the systems in place. But, given the opportunity to speak her mind, she exclaimed, “The police have proven they can’t be trusted!”

The thing that distinguished Reid from the majority of other conference attendees was her race and birthplace: black, south side of Chicago. She attended the same school as Emmet Till. If she had to put a number to it, she’d say that twenty percent of Chicago police are “good — the rest, not so much.”

A look into Chicago’s police force history can help provide context for such a statement.

According to a Jamie Kalven, a member of Stateway Garden’s Residence Council, residents of the former Stateway Gardens housing project used to jokingly call its lobbies “the policeman’s ATM machine” — they would pop in when short on cash to take drugs, money, and guns.

Former detective Jon Burge infamously ran a torture ring, using burning, beatings, and electrical shocks to force often false confessions from over a hundred black men from the 1970s through the early ‘90s.

Ronald Watts, the alleged head of the police-run drug ring, was arrested after stealing thousands from a drug courier who turned out to be an FBI informant.

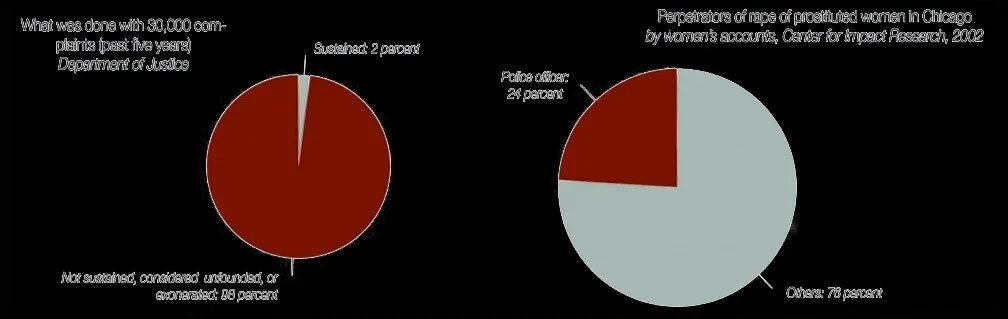

Some officers have even stolen sex. A 2002 study found that “twenty-four percent of [prostituted] women on the streets who said they were raped stated a police officer was the perpetrator, while about one-fifth of other acts of sexual violence against women on the streets was attributed to the police.” The study was conducted from a time known as the Burge years, but affects the perceptions Chicago communities have of police even now.

Graphic by Rachel Naffziger

Of 30,000 misconduct complaints filed over the past five years, only two percent were sustained, according to a report by the Department of Justice (DOJ) released January 13. The report continues:

“The City does not investigate the majority of cases it is required by law to investigate…. Some of these investigations are ignored based on procedural hurdles in City agreements with its unions, but some are unilateral decisions by the accountability agencies to reduce caseloads and manage resources. And many misconduct complaints that avoid these investigative barriers are still not fully investigated because they are resolved through a defective mediation process, which is actually a plea bargain system used to dispose of serious misconduct claims in exchange for modest discipline. Regardless of the reasons, this failure to fully investigate almost half of all police misconduct cases seriously undermines accountability.”

-page 8

“So the law is paralyzed, and justice never goes forth.”

The DOJ ultimately found a pattern or practice of force that violated the Constitution, based on an investigation of the CPD’s force practice and analysis of hundreds of incidents of force. They write:

“The City and CPD acknowledge that this trust has been broken, despite the diligent efforts and brave actions of countless CPD officers. It has been broken by systems that have allowed CPD officers who violate the law to escape accountability. This breach in trust has in turn eroded CPD’s ability to effectively prevent crime; in other words, trust and effectiveness in combating violent crime are inextricably intertwined.”

-pages 1 & 2

A Chicago Tribune poll of registered voters in Chicago released last February found that 53 percent of white respondents did not think the police treat everyone fairly, while 33 percent did. Eighty-five percent of black respondents said “No,” while just 6 percent said “Yes.” Sixty-nine percent of Hispanics said “No,” while 23 percent said “Yes.”

Cafe Jumping Bean is an anchor establishment in Pilsen.

People give Pedro looks when he wears his Chicago Police Department uniform in public.

But off duty, without his uniform, he blended in with everyone else at the Cafe Jumping Bean, where his interview was held (his name has been changed for his safety). Except for his job, little sets Pedro and his wife (who was also present) apart from the surrounding neighborhood — she came undocumented from Mexico, and they met in their parish choir on the south side. Policing pays better than any other job Pedro could get.

As a teenager, he hated the police. They would rough him and his friends up as they left school on the south side. “They would take their shots, make us kneel down, throw our stuff on the ground and laugh,” he said quietly. Pedro knows if he wanted to do the same thing now, he could get away with it. The community’s knowledge of his ability to abuse power makes it difficult for him to serve and protect them:

“[Parents] tell their kids, ‘Don’t talk to the police, don’t talk to the police!’” We try [to get to know people]. At least I do, I can only speak for myself. I try, but people just turn away sometimes,” he said.

“The kids will never, ever, ever go to the police,” said Pastor Keith, an Englewood resident who pastored there for 35 years. “Families, even when their own kid gets shot, they’re gonna say, ‘We don’t trust the police to take care of it, we’ll take care of it on our own.’… It just always seems to bite you, when you call the police.”

“Families, even when their own kid gets shot, they’re gonna say, ‘We don’t trust the police to take care of it, we’ll take care of it on our own.’… It just always seems to bite you, when you call the police.”

- Pastor Keith

In his experience, the police lost the respect of the neighborhood by ignoring their own rules: they’d run stop signs and red lights without their lights on, just to get places faster; they busted in his door once without a warrant; he informed one of their cases once, but they gave his name out, putting his life in danger. They never seemed to get the right guy, though the neighborhood “knew” who did what. The lack of trust between law enforcement and many Chicagoans impedes good police work.

Phil Sipka is the owner of Kusanya Cafe in Englewood.

Phil Sipka, an Englewood resident, runs a coffee shop and interacts with people of all walks of life: “pharmaceutical” dealers, moms, cops, and kids. He speculated that police become detached from those they police, just as ER workers can become detached from the suffering of their patients. That lack of empathy can allow for cruelty and abuse.

A selective lack of empathy alone might not account for this the CPD’s pattern or practice of unconstitutional use of force, but add fear to the equation, and it makes sense to Sipka. “That’s the problem,” he said; “you can’t serve a person that you’re afraid of. I don’t know what the solution for that is.”

Pastor Keith had a similar perception: “They’re just as scared as the kids on the street…They know they’re moving targets… [because some people] want to control the officers on the street.”

Pedro agreed. “I’m in more physical danger [now] than when I started. Twenty percent of the time you arrest somebody, something is going to go wrong,” he said. “If you let people get to you, within a few years you’ll be treating people like crap… hating everything, everybody.”

CPD’s suicide rate is 60 percent higher than other police forces.

“It’s honestly on how much you can take,” he said. “We carry a gun with us wherever we go. At any time you could point it at yourself.”

He estimated that 60 to 70 percent of his coworkers were greatly affected or even had PTSD, exhibiting symptoms around five years in. But the CPD culture discourages seeking help, even though it is available. When asked what would allow an officer to seek help, he answered, “A good partner, a good friendship… someone you can trust. Supervisors you can talk to. Someone you can go to without them opening their mouth and making fun of you.”

“For the wicked surround the righteous…”

Pedro loves his job, loves getting to know his beat. It depends on who he gets to work with though, he said. “If you work with somebody, who if as soon as they pull up to somebody they’re screaming ‘Go get the hell out of here, don’t stand there!’… for me, I can’t work with somebody like that.”

Pedro has never reported any police misconduct, for fear of backlash. “If you see something and know it’s not right,” he began, and then his wife interjected, “You don’t say anything.”

Officer Pedro has never reported any police misconduct, for fear of backlash. “If you see something and know it’s not right,” he began, and then his wife interjected, “You don’t say anything.”

Snitching has consequences. “They can mess with you in a number of ways,” he said. “It’s just more and more stress on the person for trying to do the right thing.”

Last May, two officers, Shannon Spalding and Danny Echevaria, won a whistleblower lawsuit and settled for $2 million. According to Judge Gary Feinerman, the story of the two officers’ efforts to expose a police-run drug ring “purports to show extraordinarily serious retaliatory misconduct by officers at nearly all levels of the CPD hierarchy.”

Other officers were angered by their lawsuit. Retaliation allegedly ranged from the almost honorable — attempting to get them fired and refusing to protect their safety — to the humiliating — Spalding found a pile of excrement in her mailbox, with a note: “Since you like s*** so much, thought you’d enjoy this.”

“‘God help them if they ever need help on the street,’” Rivera [Chief of Internal Affairs] quoted their commander as saying. “‘It ain’t coming.’”

- The Intercept

According to Johnson, officers who know and use the ropes can yell a sort of “code word” over the walkie talkies to protect themselves from the consequences of their actions in the field.

Legally, he said, so long as an officer is recorded as saying “stop resisting,” whatever actions that follow are justified. David Johnson believed he saw officers exploit the loophole by screaming the code word when the arrestee was not resisting at all. Once the word had been said, force could be used with abandon and be justified as self-defense, even to the point of killing someone. Johnson’s belief that such a loophole exists is reflective of a culture of deep mistrust of the police.

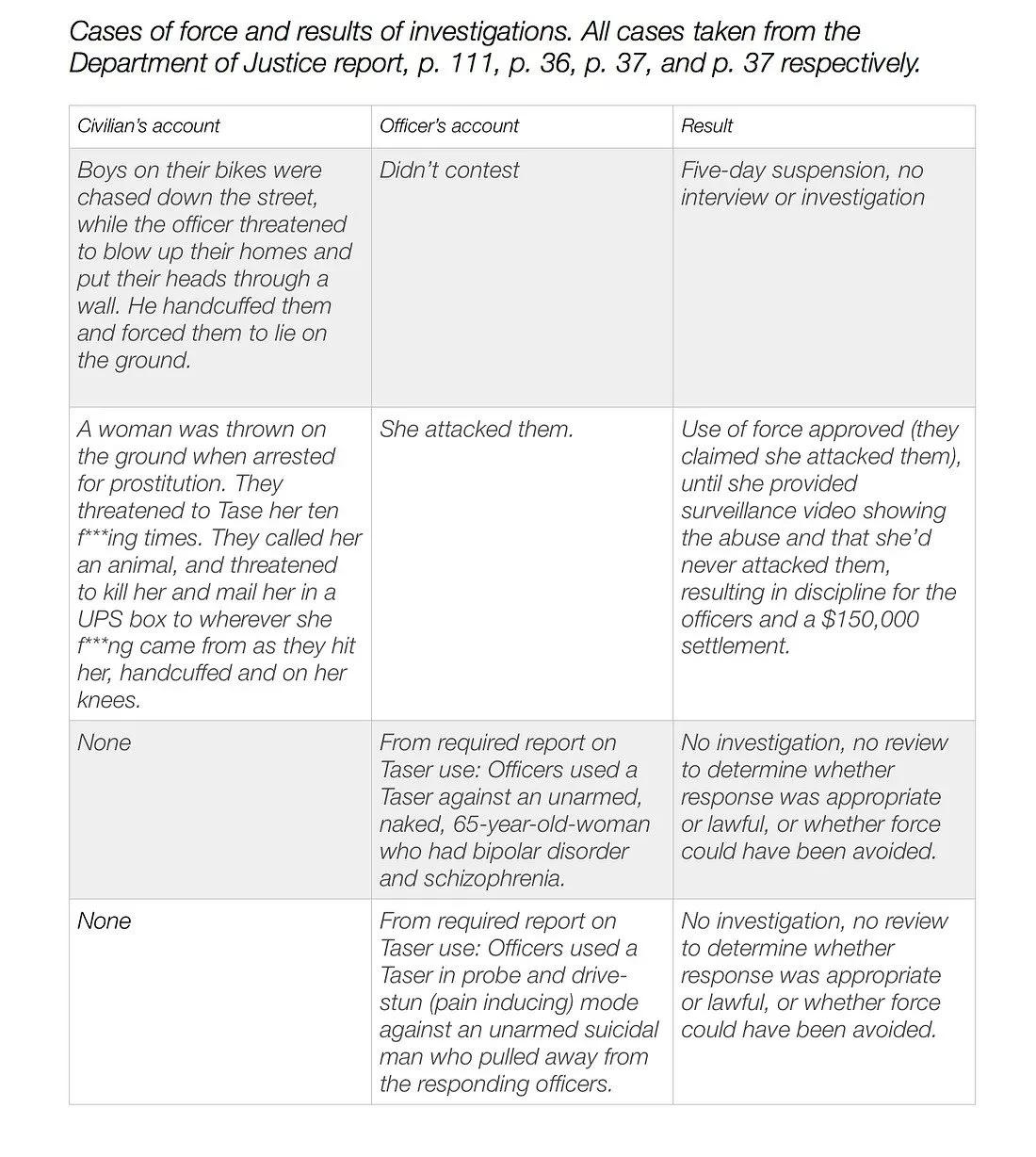

Cases of police force and the results of investigations. Source: DOJ report.

There’s also a culture of mistrust within police ranks; “[retaliatory conduct and silence] is part of the culture,” explained Pedro, “but in order for that to change there would have to be a lot of people fired. A lot of people. But to get rid of it or to stop it… It’s just too many people that know a lot of people that cover up for them. It’s just way too many people.”

“…so justice goes forth perverted.” (Habakkuk 1:3–4)

Michael Allen, senior pastor of Uptown Baptist Church, is careful to instruct congregants not to make judgments on highly publicized cases before all the facts are known. He is deliberate and measured, a peacemaker. But he too, has seen the police abuse their power.

Members of his congregation who have records have been stopped, handcuffed, and driven into opposition gang territory “knowing that if they are seen, they’ll be a target to get beat up, shot at, or killed,” he said.

Graffiti in Little Village

Sometimes, residents feel as if the government has abandoned them. Robert Brown, a bus driver from Austin attempted to start a community center to give kids somewhere to go after school. He worked hard to get government funding, but when he was unable to obtain it, the community center became a dream of the past.

He also noted that the police seem to have disappeared from his neighborhood. In the ’90s, he and his neighbors felt that the police presence was a positive thing. They even nicknamed an officer “Officer Friendly.”

Today, even Brown’s opinion of the justice system has been tainted: his son was accused of knifing another kid in a fight. Brown does not believe the story is accurate; nonetheless, it will lead to a permanent stain on his son’s record.

According to the Department of Justice;

“It has never been more important to rebuild trust for the police within Chicago’s neighborhoods most challenged by violence, poverty, and unemployment… Chicago must undergo broad, fundamental reform to restore this trust. This will be difficult, but will benefit both the public and CPD’s own officers. The increased trust these reforms will build is necessary to solve and prevent violent crime. And the conduct and practices that restore trust will also carry out an equally important public service: demonstrating to communities racked with violence that their police force cares about them and has not abandoned them, regardless of where they live or the color of their skin. That confidence is broken in many neighborhoods in Chicago.

At the same time, many CPD officers feel abandoned by the public and often by their own Department. We found profoundly low morale nearly every place we went within CPD. Officers generally feel that they are insufficiently trained and supported to do their work effectively. Our investigation indicates that both CPD’s lawfulness and effectiveness can be vastly improved if the City and CPD make the changes necessary to consistently incentivize and reward effective, ethical, and active policing. While it will take time and concerted focus to implement all of the necessary changes, [involving use of force, accountability, training, supervision, officer wellness and safety, data collection and transparency, promotions, and community policing (p. 150–160)] a strong sign of a genuine and unalterable commitment to such change could increase officer morale more quickly, especially among the countless good officers within CPD who police diligently every day, and who disapprove of some officer conduct they see — and many of whom quietly told us how eager they are for the kind of change that can come only from an investigation like the one we have just completed.”

-page 4

Some are less quiet in their eagerness.

Some officers attend events like Pray Chicago and openly pray against the problems they see in the force. Sipka remembers an officer who recently visited the coffee shop. “He just wanted to come in and literally talk about different ways to rebuild trust in the neighborhood,” Sipka said. “And he cares. I believe it.”